Tom Lehrer, wickedly funny musical satirist whose subversive ditties caused outrage and delight

Tom Lehrer, who has died aged 97, wrote and performed such subversive ditties as Poisoning Pigeons in the Park and The Masochism Tango, and was a sensation during the satire boom of the 1950s.

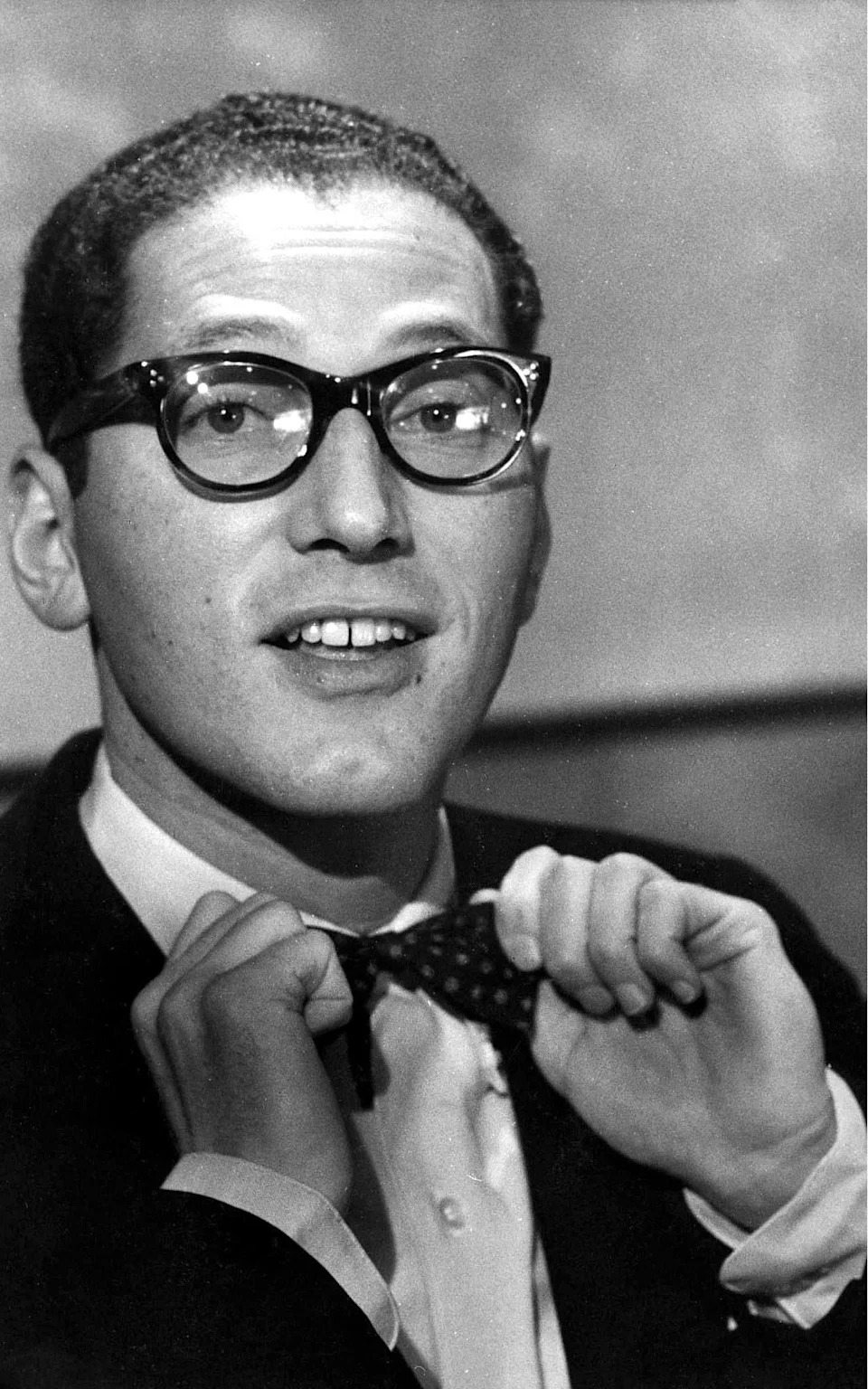

A lanky figure with cropped hair, horn-rimmed glasses and a sardonic smile, Lehrer had a clear eye for phoniness and folly and a genius for subversive juxtapositions of words and ideas: “I ache for the touch of your lips, dear,” he wrote in The Masochism Tango, “But much more for the touch of your whips, dear./ You can raise welts/ Like nobody else/ As we dance to the Masochism Tango.”

In other numbers, a trite Irish ballad celebrates a succession of murderous misdoings; a romantic love song is subverted into the lament of a lover who has murdered his girlfriend and cut off her hand as a keepsake: “The night you died I cut it off/ I really don’t know why./ For now each time I kiss it/ I get bloodstains on my tie.” “You know,” Lehrer concluded after the end of this last piece, “of all the songs I have ever sung, that is the one I’ve had the most requests not to”. “Mr Lehrer’s muse [is] not fettered by such inhibiting factors as taste,” observed The New York Times.

Lehrer became a cult figure on both sides of the Atlantic for his astute parodies of composers ranging from Mozart to Gilbert and Sullivan and from Cole Porter to traditional melodies popular in what Lehrer called “the folk song scare” of the 1950s. These became the vehicles for send-ups of boy scouts, religion, love, plagiarism and the old college tie, and dealt with such unmentionables as venereal disease, incest, pornography and drug addiction.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_8pokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_gpokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeNot everyone saw the joke. The Herald Tribune critic panned Lehrer’s songs as “more desperate than amusing” and the London Evening Standard dismissed him loftily as “obvious, jejune, and remarkably unsophisticated”.

His songs were banned by school boards in America after protests by Roman Catholic groups about The Vatican Rag (“Two four six eight./ Time to transubstantiate.”). I Wanna Go Back To Dixie was billed simply as “a typical Dixie song, all about the many delightful features of the South”, but the lyrics (“I wanna talk with Southern genn’lmen/ Put my white sheet on again/ I ain’t seen a good lynching in years”) so enraged students at Carolina University that they burned Lehrer in effigy.

On the other hand, Fight Fiercely Harvard, a parody of the glee club songs of the time, was adopted in all seriousness by the Harvard football team and remains its theme song to this day.

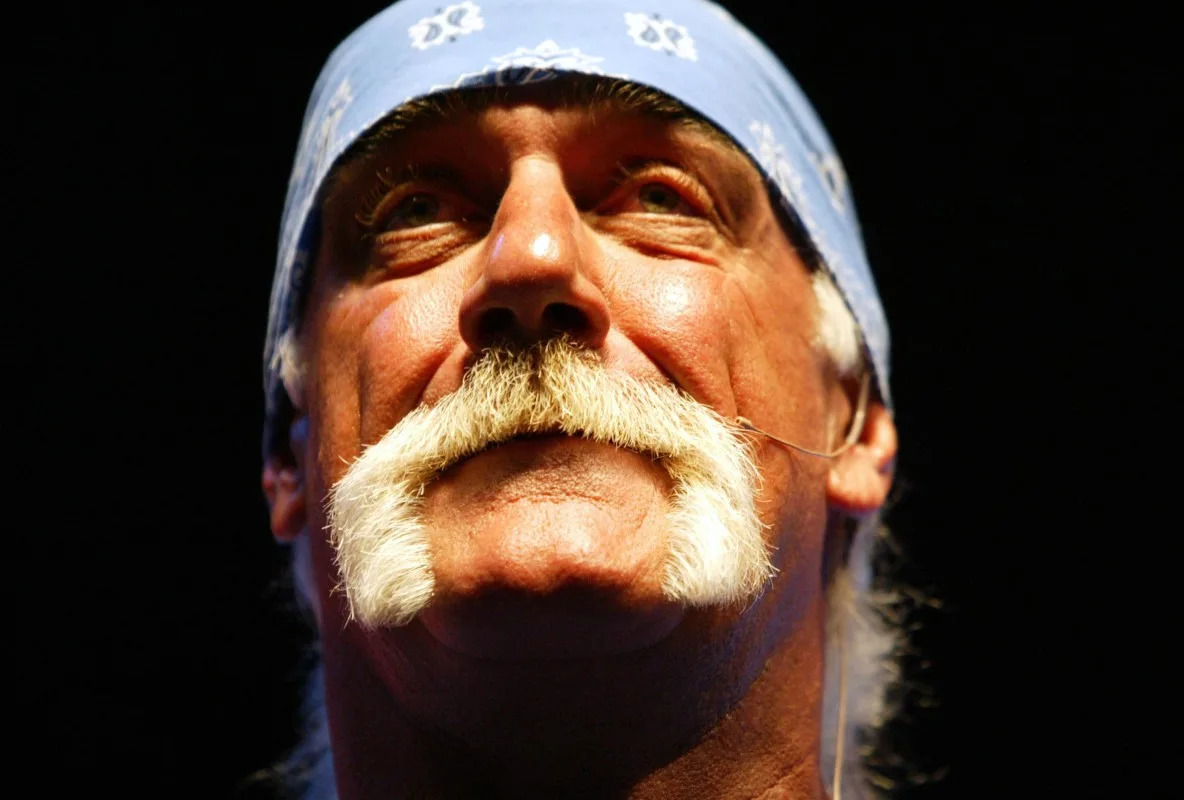

Lehrer: sent up the melodies popular in what he called ‘the folk song scare’ of the 1950s - Rex

Lehrer: sent up the melodies popular in what he called ‘the folk song scare’ of the 1950s - RexIn all, the Lehrer canon amounted to only about 50 recorded songs and three albums. In the late 1960s, after sell-out tours of the USA and Britain he retired from performing. It was widely rumoured that the muse had deserted him when the horrors of the Vietnam War made it difficult to be funny about serious things – or as Lehrer was quoted as saying (though he later denied it): “Political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.”

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_9hokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_hhokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeBut he later admitted that he had been planning to retire from the outset of his career, and that the only thing that had persuaded him to defer his departure was “the chance to visit underdeveloped countries like England”. “I don’t have to do this for a living,” he told his audiences. “I could be earning £800 a year teaching.”

Thomas Andrew Lehrer was born in New York on April 9 1928 and grew up in the cramped but intellectually stimulating world of the city’s Jewish immigrant community. His father manufactured ties, but it was from his mother that he inherited his musicality and sense of humour. He would recall how, after being pestered by a dance teacher for dropping out of her class, his mother had explained with perfect deadpan that she had just had both legs amputated so she hoped the teacher would forgive her.

Visits with his mother to musical theatre ignited a passion that led him as a child to insist on changing his piano teacher from a classical pianist to one who was willing to indulge his desire to play show tunes. He began writing tunes himself when he was seven or eight and was sent on summer camp with a boy called Stephen Sondheim, who became his musical hero.

At the same time, Lehrer was showing a precocious talent for mathematics, and at the age of just 15, he went up to read the subject at Harvard. His mathematical and scientific background would occasionally enter his lyrics, as in The Elements and Lobachevsky, a rollicking ditty about scientific plagiarism, based on Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, a Russian mathematician who developed a form of non-Euclidean geometry. In a typical Lehrer in-joke, the plagiarism was not Lobachevsky’s but Lehrer’s own plagiarism of a Danny Kaye song.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_a9okr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_i9okr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeLehrer’s first serious efforts at song-writing began in his days as an undergraduate, when he started performing at parties and at Harvard functions. His reputation spread outside the university to the town of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he began singing in night clubs and cabarets.

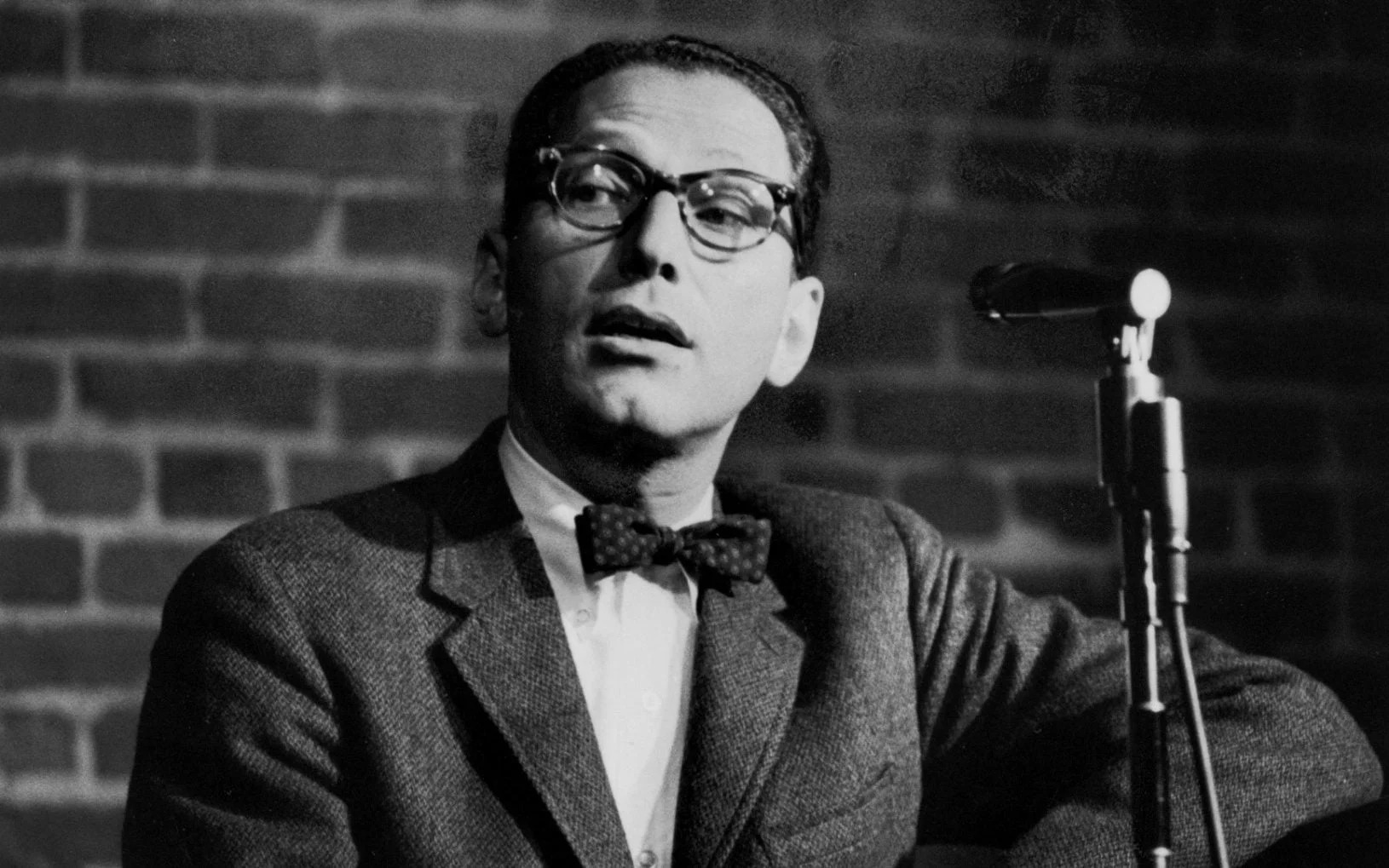

Lehrer: a genius for subversive juxtapositions of words and ideas - George Konig/Rex Features

Lehrer: a genius for subversive juxtapositions of words and ideas - George Konig/Rex FeaturesAfter a few years, however, he began to tire of performing the same songs over and over again. Polling his concert audiences, he calculated that he could find 300 customers for a Tom Lehrer record. But the record companies were not interested, so in 1953 he recorded his first album, The Songs of Tom Lehrer, himself. As his songs were banned by American radio stations as too crude, he had to rely on the record to spread his music. After several months of local sales, he began receiving orders from around the country as Harvard students took the album home to share with their friends.

After leaving Harvard, Lehrer spent a year singing songs in cabaret and trying to avoid call-up into the armed services, “but it got too tiring so I let them take me in”. He was given a desk job in Washington and had two “wonderful years” working with Harvard men and civilian PhDs. When he later wrote the satirical It Makes A Fellow Proud To Be A Soldier, he admitted it did not represent his attitude to the army at all since he had loved every moment.

He left the army just as the concept of a touring popular music concert was emerging. Finding that he was still in demand, Lehrer gave his first concert that year at Hunter College, and spent the next three years touring most of the English-speaking world. In the British satire explosion of the late 1950s, he was adopted as a sort of mascot Yank and even dined with Princess Margaret: “She thought I was Danny Kaye, whom she fancied,” Lehrer recalled. “Instead I was me and was dull.”

Even at the height of his celebrity, however, Lehrer knew that live entertainment was not his cup of tea. “I wouldn’t want to do this all my life,” he said in 1957. “It’s okay while I’m still an adolescent.” (He was nearly 30 at the time.) His second album, An Evening (Wasted) With Tom Lehrer, was recorded in 1959, as a farewell, during a concert at Harvard. “I figured that if the record was out, who would want to come hear me?” he said.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_bdokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_jdokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeHe returned to Harvard, where he had already embarked on a doctorate, but soon decided he would rather teach than research: “I kept saying to myself that if I ever get this dissertation written, I will never have to do any research again. Then I realised that I must be telling myself something, so I decided enough is enough.” He held teaching appointments at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard and Wellesley, and also worked for several defence contractors (including the Atomic Energy Commission’s nuclear laboratory in Los Alamos).

Although he was no longer performing, Lehrer’s songwriting career was not yet over. In 1964, NBC began broadcasting an American version of the British satirical show That Was The Week That Was. Lehrer started to send in songs for the show and found they usually used them. In contrast to his earlier black comic parodies, his songs for TW3, including numbers like Pollution and Wernher Von Braun (“Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down?/ ‘That’s not my department’, says Wernher von Braun”), hit a more acid political note.

By 1965, Lehrer had enough new material to fill another record and, to assure himself that audiences would actually enjoy the material, he did a four week stint at the hungry i, a San Francisco club, recording That Was The Year That Was during his last week there.

It was his last LP of satirical songs, though he recorded a few educational numbers for the children’s television shows Sesame Street and The Electric Company. Generally, though, when people asked him to write a new song about current issues, he likened it to “asking a resident of Pompeii for some humorous comments about lava”. He even admitted encouraging rumours of his death in the vain hope of cutting down on unwanted requests.

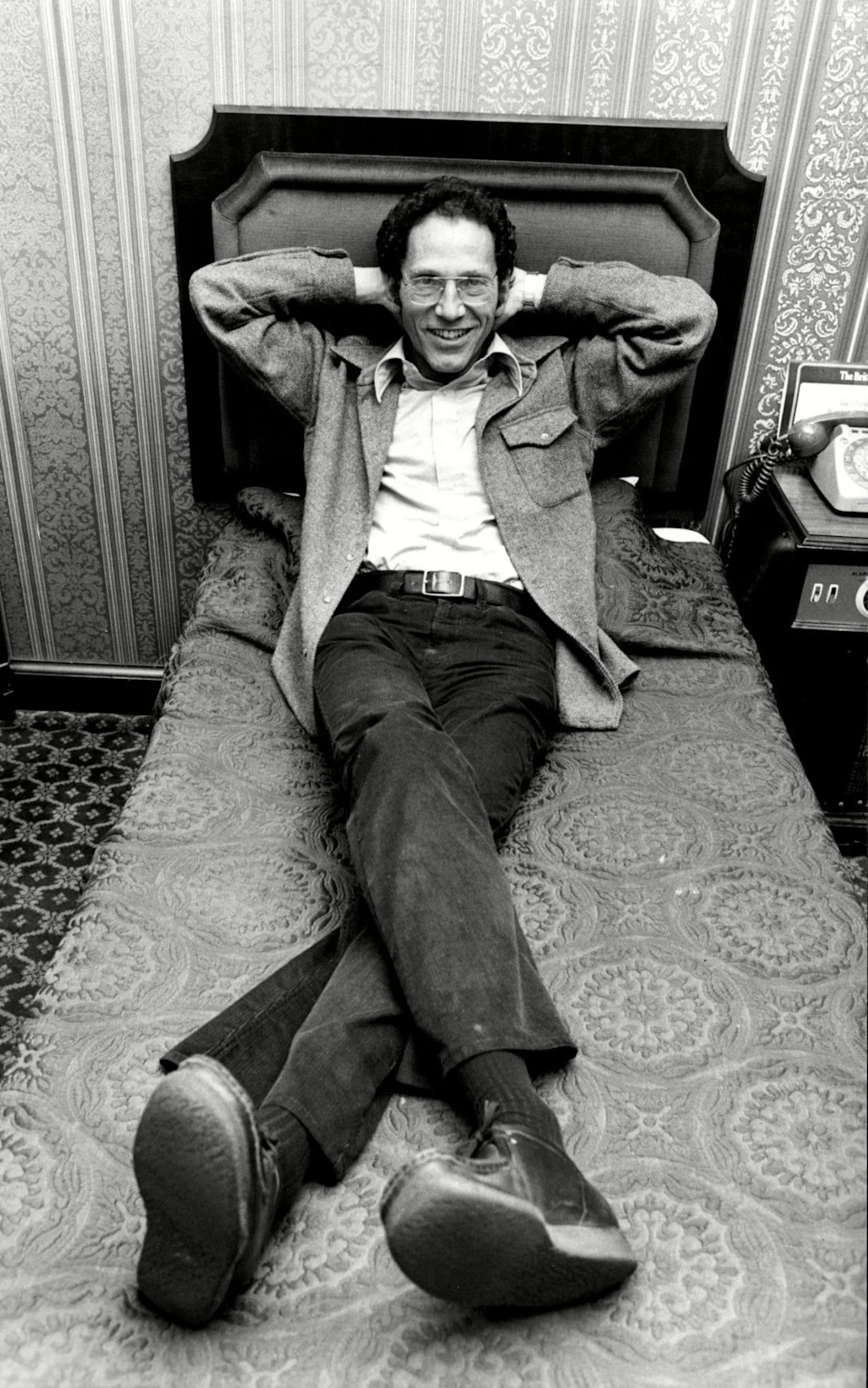

Lehrer in retirement in 1998: in 2022 he put all his songs into the public domain

Lehrer in retirement in 1998: in 2022 he put all his songs into the public domainLehrer banked his royalties and moved on, spending half the year at Harvard and the other half at the University of California at Santa Cruz teaching mathematics. “I teach the application of mathematics to social science,” he explained. “Actually there aren’t any, but I manage to make it stretch out”.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_cdokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#_R_kdokr8lb2mav5ubsddbH1_ iframeLehrer, it seemed, would have been content to live out the rest of his life in the classroom, but in 1978, the British theatre producer Cameron Mackintosh approached him about creating a musical revue of his songs. As Mackintosh had just produced a well regarded revue of his hero, Stephen Sondheim, Lehrer agreed, and two years later Tomfoolery opened at the Criterion Theatre in London. The success of the show brought Lehrer back into the spotlight just long enough for him to explain why he had stopped performing and writing songs. “What are laurels for if you can’t rest on them?” he asked.

Lehrer’s songs retained an enthusiastic following in the 21st century – his nuclear holocaust ditty We Will All Go Together When We Go seemed more relevant than ever – and when representatives of the rapper 2 Chainz sought permission to sample his song The Old Dope Peddler in 2012, he replied: “As sole copyright owner of The Old Dope Peddler, I grant you mother------s permission to do this. Please give my regards to Mr. Chainz, or may I call him 2?”

In 2022, uniquely for a recording artist, he announced on his website that he was relinquishing all copyright claims on his work, putting all his songs into the public domain.

Tom Lehrer never married and always brushed away questions about his private life, describing himself as “fundamentally a loner”, but with a few good friends.

Tom Lehrer, born April 9 1928, died July 26 2025

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.